The Tylenol Tale Gets an Ending

Several years earlier, Lewis had been arrested for an unrelated murder but couldn’t be prosecuted because of a technicality: he had not been read his rights. In 2004, he was nicked for aggravated rape involving the drugging of an alleged victim but was not prosecuted because she decided against cooperating. Among Lewis’ other pastimes was regaling those who would listen precisely how he would have carried out the Tylenol homicides if he were to have committed them. Which he hadn’t. Heh. For Lewis, crime always paid.

One of the great legacies of the Tylenol case is J&J’s foresight to have developed tamper-resistant packaging. I’m less impressed with the mythology surrounding the case because, in addition to being fantastical, it has taught people false lessons about what damage control can and cannot accomplish. After all, if it were that formulaic, wouldn’t everybody be doing it?

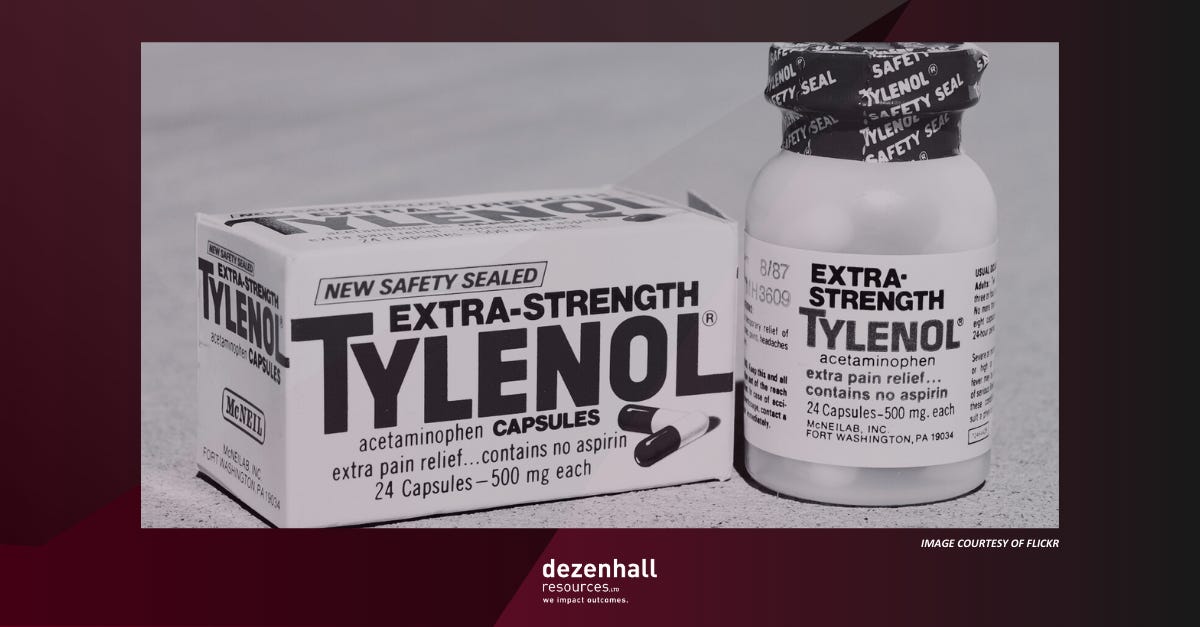

The legend goes like this: After seven people (including a child) died after taking Tylenol pain relief capsules, mainly in the Chicago area, manufacturer Johnson & Johnson immediately recalled the product, apologized, and introduced tamper-resistant packaging that revolutionized safety. The company retained a vast majority of its market share and became the case study in good crisis management. As I pointed out in my book Glass Jaw (and other books and articles), the truth is more complicated.

When the crisis broke, I was working in the White House, and there was buzzing in the hallways about the murders. There was a nationwide panic. I remember a colleague throwing away her Tylenol bottle, an act being repeated everywhere. After all, it was a tangible action that could be taken to avoid injury or death. The search for the killer was on, as was some kind of understanding of how the cyanide had found its way into a popular pain reliever. Had it happened at the manufacturing level? Was it due to a production accident? Industrial sabotage? Or were we dealing with a lone murderer?

J&J’s CEO, James Burke, appeared on 60 Minutes and demonstrated what the company was doing to address the crisis. The avuncular boss acquitted himself very well. The company also paid hundreds of millions in settlements, which hagiographers rarely mention. Most impressive, however, was that J&J had in its pipeline tamper-resistant packaging that they began using in containers, pioneering the entire safety-in-packaging discipline. Before very long, Tylenol sales rebounded. It was a happy ending from a B-school and shareholder perspective.

What has happened since that time has been fascinating to watch as it coincides with my career in crisis management. Over the years, I have been in dozens of meetings when someone has arched an eyebrow and claimed to have worked on the Tylenol case at this or that PR firm. This is bullshit of breathtaking proportions. In most cases, these flacks were either outright lying or taking an obscenely attenuated link — such as working on an account for some other J&J product where the case may have been mentioned at a water cooler — and positioned it as direct personal involvement. This would be like me saying that because I was one of many kids working in the Reagan White House, I had engineered the end of the Cold War and an unprecedented bull market (a claim that my late mother would have happily promulgated).

The Tylenol legend is predicated on two inaccurate narratives. The first is that J&J instantly recalled the product. The company did not. It could not have because they did not and could not have known what was happening “instantly,” the line used in the movie The Insider where the case was mentioned. When it comes to mass-produced and distributed products, nobody knows anything instantly when millions of units are involved. It wasn’t until a week after the first deaths when J&J and retailers realized that two people in the same family had died and that taking Tylenol may have been a common denominator. A nurse was the first to point out the possibility of tampering, but law enforcement hadn’t taken her seriously because it sounded so preposterous. The product was recalled after retailers like Walgreens and CVS pulled it from their shelves.

A consulting firm that, according to the late J&J executive Larry Foster, who really did manage the crisis, went on a forty-year road show where it merchandized a fantastic version of how they managed the controversy. The firm ensured that it became an MBA school case study. To this day, almost everyone familiar with the crisis believes this version. It remains the crisis management gold standard and the kind of hyperbolic business development pitch that defines the industry today. Foster had been astonished at what the case study wrought in terms of shameless self-promotion and didn’t hesitate to call flacks to account when he heard they were falsely claiming credit. He would occasionally share with me the letters he had sent the fabulists.

Not all crisis cases are of the same variety any more than diseases are. A child’s scraped knee must be treated differently from an incurable genetic condition. One of the main factors in attacking a crisis is provenance. In Tylenol’s case, the product was attacked from the outside by a deranged murderer. No one was suggesting that J&J was harming people to cut costs or experiment on the public. I call cases like Tylenol “sniper” crises because they are random and externally generated. This is different from, say, selling a drug that a company knew to be dangerous in and of itself and that injured countless people. I call the latter “character” crises because the integrity of the product and company is in question.

The Tylenol murders presaged an era in which one lone bandit can damage a target that is far more powerful by most other measurements, an ongoing theme in Glass Jaw. It is noteworthy that after 40 years, the resources of the U.S. government and J&J could never bring Lewis to justice, an outcome that should make us all shiver.

Another legacy is that the Tylenol case, however flawed, catalyzed the industry where I was an early player. I feel privileged to have been on the scene at the right time — even though to be clear, I had nothing to do with the Tylenol crisis. I was too busy single-handedly ending the Cold War, an achievement that has been consistently overlooked.