Wait Till They Get a Load of Me!

I’ve been following the murder trial of South Carolina lawyer, Alex Murdaugh, for a few reasons. The first is that I am riveted by true crime. The second is that there are parallels between this violent crime and the white-collar cases I’ve worked on in crisis management.

There are crimes committed by the desperate, and there are crimes committed by the blessed. Where they differ is that the crimes of the desperate are often done by those we deem to be at the bottom of the great food chain of life. Someone like Murdaugh, accused of killing his wife and son, inhabited the top rung of what is known as the South Carolina Low Country, due to the terrain not its morality.

In the cases I’ve worked on, Masters of the Universe often have done what they did because, at some level, they couldn’t abide that there were bigger masters out there. They wanted to be higher than high, huger than huge. They would only be legitimate once their net worth cleared a billion; and if they got there, they’d still feel inferior to someone worth double billions.

On a deep level, we are all primates sniffing each other on the African plain trying to assess how high we smell instead of the primates next door. On the one hand, we can’t help it; we’re hardwired this way. On the other, we can help it because we have free will; we can choose not to play. If a neighbor doesn’t want to hang with me because the square footage of my house is significantly less than his, I can choose to be friendly with people who aren’t asses. This task is easier for some people than it is for others.

Alex Murdaugh is a type. A glib frat boy used to getting what he wants because of his name. An easy smile and pleasant personality couldn’t have hurt. It must have been great. Contrary to tedious essays in self-help columns, adversity is awful. What doesn’t kill you actually can come close to killing you. However, adversity’s one benefit is that it teaches you to calibrate risk accurately. You don’t come to think you’re unique in terms of how the odds will shake out.

As a crime writer (in my other life), I’ve learned that to write criminals off as bad people isn’t enough. Sure, most of those who commit terrible crimes are bad people, but one of the things that go hand in hand with criminality is a sense that even if you behave poorly, the consequences that descend upon most people won’t descend upon you.

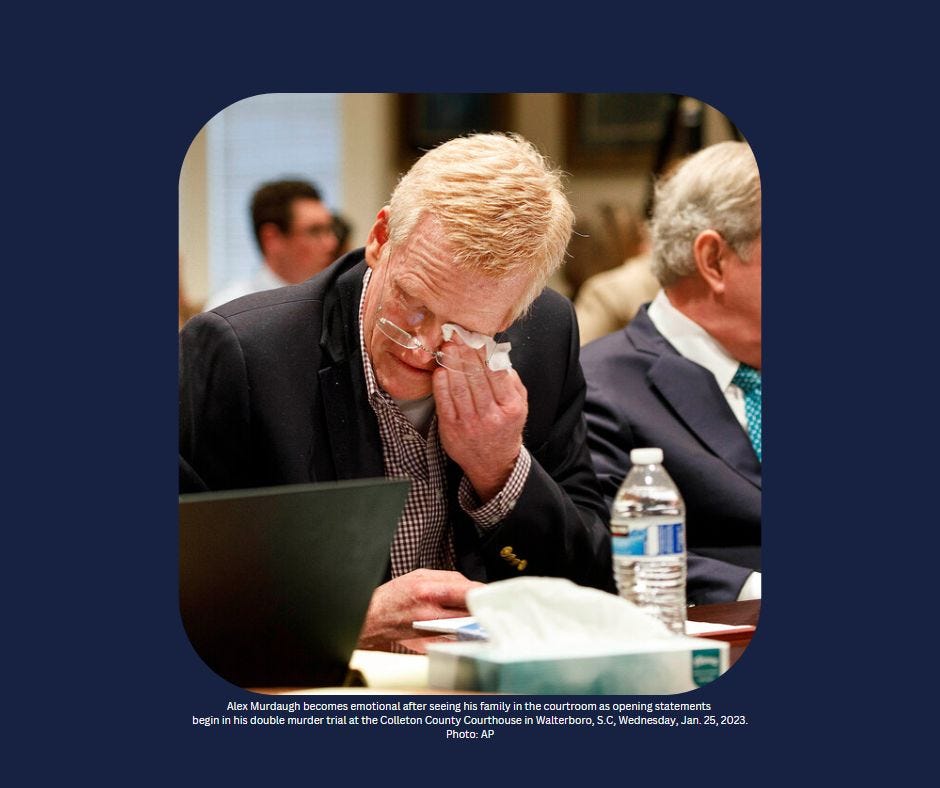

Some of those commenting on Murdaugh’s demeanor and testimony in court have sneered about his crocodile tears. My experience with scandal figures leads me somewhere different. I think the man is genuinely distressed. He can’t believe where his life — his exceptional life — landed him. It’s one thing to think about committing a crime and another to experience it unfolding. If, in fact, he killed his wife and son, seeing them blown apart could still have been traumatizing. And finding himself without money, without a family, and for the first time ever without relevant status surely would rock his world.

As Murdaugh testified, I thought about some of my famed white-collar scandal clients, how badly they wanted to testify, and how their lawyers balked. They mistook a belief in their innocence for a belief in their own charisma. The two are different things. I vaguely remember one of these clients saying something about looking forward to having the chance to make eye contact with female jurors, as if he were George Clooney. And that is what his life experience had taught him. In his narrow little world, he was George Clooney. And in Alex Murdaugh’s little world, he was some combination of Clooney and Prince Charles. Some of his tears may well be for his lost wife and son, but others are for his lost life — and potentially his lost specialness. In the meantime, he may still be thinking, “Wait til the jury gets a load of me!”

A spray of blood and brains changes things. It makes people wonder whether they’ve seen things wrong all along, whether they’ve been gullible, whether they’ve let you get away with too much and for too long. It makes us wonder why we were foolish enough to think you were special in the first place.

What many of my clients in extremis have wanted is to get their prestige back, independent of what they have been alleged to have done. Some want redemption, but redemption is work and takes time. No, it’s prestige they want and a reversal of time’s arrow. My talents extend only a little.

It always surprises students when I tell them my most sincere clients are big companies. They have the resources, leadership and time horizon to recover. They know that to get back to where they were, they will have to persuade people not to abandon them. Corporations may not have much of a conscience, but the people within them do. They also have fears, families and the dread of mortality.

Masters of the Universe, even in a small universe like the Low Country, have different nightmares, namely a dread of not being worshipped and acknowledged as Gods among mortals. This screws with their gyroscopes and bollixes their abilities to process likely consequences. In Murdaugh’s case, the prescription drugs didn’t help, but the real opioid in his bloodstream was the reality of absurd privilege. We’ll see soon enough how special the jury thinks Alex Murdaugh is. Nothing would surprise me because, in the end, it turns out that some people really are special, if not in the eyes of God, here among those of us on earth.